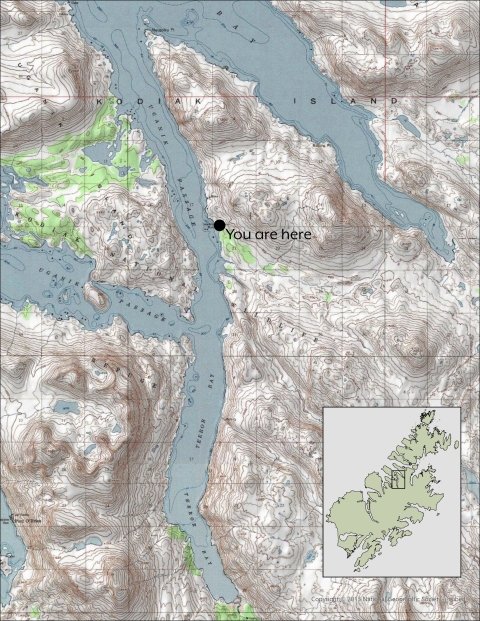

Tens of thousands of years ago, tongues of glacial ice carved steep mountains and narrow bays into Kodiak’s coast.

One of these waterways is Quluryaq—Terror Bay and Uganik East Passage. The region’s mountains have a dense cover of grasses, brush, and stands of Sitka spruce. They are home to brown bears, river otters, red fox, and a few introduced species including Sitka black-tailed deer and mountain goats. In thewaters of Quluryaq, there are clams, mussels, kelp, marine fish, harbor seals, sea lions, and salmon bound for coastal streams.

Quluryaq has a long human history, from its use by Native fishermen to recent settlement by miners and bear hunters. Today, it is part of the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge. Here people commercial fish, guide sport hunters, harvest subsistence foods, and enjoy the wilderness.

Alutiiq/Sugpiaq people settled Quluryaq over 7,500 years ago, harvesting from its productive waters and lush uplands.

The remains of their settlements dot the coastline, revealing the places ancestors lived, camped, harvested, and celebrated life. Above this small beach there was once a settlement. Native people visited here repeatedly. The tools and materials they left behind suggest that they stopped to fish and collect clams and mussels.

Beneath the plants that cover the hillside, there is a thick deposit of midden—shell, animal bones, and tools. Cobbles used as net weights and slate ulus used for butchering suggest residents harvested salmon and cleaned their catch. Alutiiq fishermen likely used beach seines to catch salmon heading up the bay. Fishing probably took place in late summer when salmon are plentiful here.

PROTECT THE PAST: If you find an artifact, please leave it. Take a photograph, not the object. Respect and protect Kodiak's history.

Homestead

A Remote Mine

In the early 20th century, American settlers explored Kodiak Island for mineral deposits.William Baumann, an agricultural worker from Minnesota, registered a mining claim in the 1920s with two partners. Baumann and his wife Elizabeth Kalmakoff, an Alutiiq woman from Kanatak, built a log cabin about a kilometer south of the mine. The Baumann’s spent their retirement years gardening, keeping chickens, and prospecting.

Kodiak bears and the National Wildlife Refuge

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt created the KodiakNational Wildlife Refuge to protect brown bears and their habitat. The Baumann property became an inholding in the refuge. A regulated annual bear hunt, led by licensed commercial guides, became an essential part of wildlife management in the refuge.

“Even the bear hunting, when I reflect on it, I don’t think it was so much about the sport of the bear hunting. . . . the guiding was a means to utilize the resources of the land. As things were changing, subsistence economies were turning into cash economies at that time, so it was a means to make a living. . . .” – Steven Helgason, 2024

Family Guiding Operations

Baumann’s daughter, Clara and her husband, Icelander Kristjan Helgason, took over the property in the 1950s. They used the remote camp as a base for commercial bear guiding. The couple, along with their son Leonard and Clara’s brother William Baumann, Jr. worked together. Later they were joined by Leonard’s son Steven.

“I should have started earlier. I didn’t know how much money was in hunting at that time..” – Kristjan Helgason, 1972

While commercial guiding provided income, it was also a lifestyle. The spring bear season lasted six weeks from April to mid-May, but the Helgasons lived in Terror Bay for much of the year.

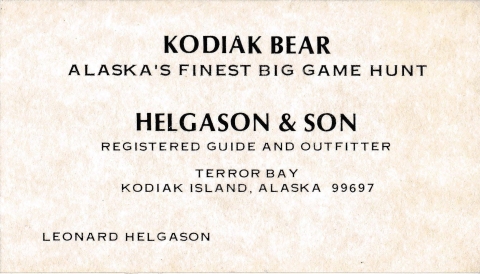

Helgason & Son: Guides and Outfitters

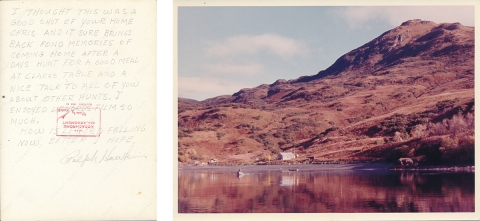

For the Helgasons and many of their guests, visiting Terror Bay was as important as the hunt. Sportsmen came from all over the United States and even the world to hunt the Kodiak brown bear and Sitka black-tailed deer. They traveled to Terror Bay on a small amphibious mail plane from Kodiak. The Helgasons led 10 to 12 days of hunting and excursions. At the camp visitors found a warm home full of local stories and subsistence foods.

The Helgasons took pride in sharing their way of life. In addition to hunting, they visited neighbors to see salmon set net fishing and shared wild foods. Clara enjoyed serving meals to her guests.

“We had some deer hunters from Anchorage, the banker, Ed Rasmuson. They all had just a wonderful time out there. And we got a letter from Ed Rasmuson, thanking us for having such a wonderful time. They said ‘We’ve hunted in many camps and that’s the nicest camp in Alaska.’ It just made us feel so good, you know.” – Clara Helgason, 1972

“She took pride in feeding the hunters and taking care of them. The hunters, they all loved Kristjan. My grandfather, he was a really good storyteller. He enjoyed all the hunters... It was a jolly time around the dinner table back in the days. They got to eat good meals. They got to taste the land.” – Steven Helgason, 2024

“…their bear guiding camp was a little bit different from some of the other ones because it was more like a home kind of feel…” – Brent Watkins, Terror Bay Neighbor, 2024

When the bear season ended in May, the Helgasons focused on commercial fishing, subsistence harvesting, tending to their property and gardens, and storing food for winter. The family lived in Kodiak and Anchorage, returning to Terror Bay for the summers. After losing her husband in 1977, Clara kept the remote camp going. She cooked for guests well into her 80s while her son and grandson guided and fished. In the early 1990s, Clara retired from remote life. She sold her property to the Kodiak National Wildlife Refuge and spent her final years in the City of Kodiak.

“I just remembered the good times and I have fond memories of it. It was a good experience being out there…” – Steve Helgason, 2024