Many vestiges of the past, like castles and Gothic architecture, are welcome sights today. They give us insight into how people lived and inspire us to reach back to the past while moving forward to the future. However, many constructions of yesteryear are far less inspiring and can be attractive nuisances at best, safety hazards at worst. Often, dams are a prime example.

Rivers and streams in New England have a long history of being harnessed to power mills and factories. Many dams today are 100 or more years old and not well maintained. They lead to problems like fragmented rivers, stalled fish migration and communities at higher risk of flooding.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and our partners are removing these barriers to help conserve vulnerable species while building safer infrastructure for people.

Something temporarily or permanently constructed, built, or placed; and constructed of natural or manufactured parts including, but not limited to, a building, shed, cabin, porch, bridge, walkway, stair steps, sign, landing, platform, dock, rack, fence, telecommunication device, antennae, fish cleaning table, satellite dish/mount, or well head.

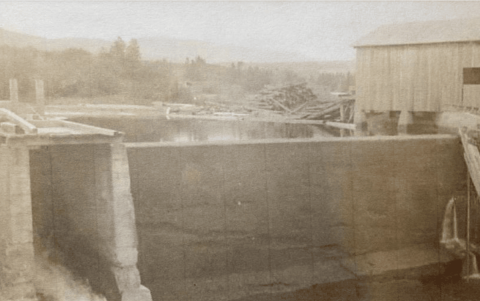

Learn more about structure showing no signs of breaching. Photo credit: Colebrook Historical Society.

The Washburn Mill Dam in Colebrook, New Hampshire, was constructed in 1929 and named after its owner, Abraham Washburn. The dam harnessed the rushing water of the Mohawk River to power a nearby sawmill for more than 40 years.

After several floods took it out of commission, the mill was closed in the 1960s due to a lack of demand for wood products from small-scale operations. The building was removed in the 1970s, leaving the dam.

Though dormant for years, the dam continued to impact the ecosystem and the local community.

Colebrook today

Colebrook is the hub of northern Coos County. The Mohawk River is a tributary of the Connecticut River, which runs through Colebrook. This far-north area of New Hampshire has some of the best brook trout habitat due to its clean water and lack of habitat disturbance.

Unfortunately, the past few decades saw an uptick in rain events that cause flash flooding in this mountainous region, where rivers run fast and overflow just as quickly. The dam didn’t help matters.

The 25-foot-high, 100-foot-long dam sat about 50 feet upstream of the bridge that carries Diamond Pond Road over the Mohawk River to a large residential community. The river runs northwest through the dam site, under the Diamond Pond Road bridge, and then flows parallel to the southern boundary of Colebrook and feeds into the Connecticut River in Colebrook’s town center.

The dam was a barrier to fish moving upstream and sediment moving downstream. During heavy rain events, it contributed to flooding of the road, limiting access to medical care. Its old, crumbling infrastructure hindered the movement of wildlife, and the water behind the dam warmed, reducing habitat for fish like brook trout that require cooler water for survival. Over time, it became clear the dam had to go.

When life knocks you down

Planning for the dam’s removal began in 2019, when project partners visited the site. Removal of the dam was a priority for the New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services Dam Bureau and the Upper Connecticut River Mitigation and Enhancement Fund.

Funding large-scale efforts like this can be challenging and require money from multiple sources.

The Service’s National Fish Passage Program provides financial and technical assistance to support projects that improve fish passage fish passage

Fish passage is the ability of fish or other aquatic species to move freely throughout their life to find food, reproduce, and complete their natural migration cycles. Millions of barriers to fish passage across the country are fragmenting habitat and leading to species declines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Fish Passage Program is working to reconnect watersheds to benefit both wildlife and people.

Learn more about fish passage . Since 1999, the program has removed or bypassed more than 3,500 barriers to fish passage and reopened access to more than 64,000 miles of upstream habitat for fish and other wildlife. Though an important program, it often lacks the capital to fully fund projects like the Washburn dam removal

The National Fish Passage Program provided $500,000 toward the Washburn dam’s removal, supplementing $650,000 secured by American Rivers, a partner in the dam’s removal.

Following an extensive planning process to ensure benefits to habitat and safety of the nearby community, preliminary plans for the dam's removal were drawn up in 2022.

American Rivers spearheaded the project, along with the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department and New Hampshire Department of Environmental Services. Despite weather challenges that threatened the project’s completion, the dam was fully removed in October 2024.

Falling apart means falling into place

Northern tributaries of the Connecticut River provide important freshwater breeding and spawning habitat for native fish. Removing barriers along the tributaries and reconnecting them to main waterways encourages genetic diversity among previously separated populations.

Removal of the Washburn Mill Dam reconnected nearly 40 miles of high-quality brook trout habitat. Jaime Masterson, a fish biologist with our Central New England Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office who was involved with the project since the beginning, says Colebrook presents an optimal area for brook trout due to its cold, clean water, especially as climates change.

“With climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change , this area of the East Coast will be one of the last strongholds for brook trout because it can maintain livable conditions for them, even with temperature increases,” Masterson said.

In addition to brook trout, removing the dam will benefit other native species, including longnose and white sucker, slimy sculpin, burbot, longnose and blacknose dace, creek chub, rainbow and brown trout, and wood turtle.

As for the surrounding community, they were happy to see the dam go.

One neighboring landowner across the Diamond Pond Road Bridge experienced intense flooding during weather events thanks to the dam. Another landowner experienced erosion due to the sharp angle the dam created with the stream; once it was gone, we restored the streambed and straightened the stream to decrease erosive effects.

With the dam removed, brook trout monitoring by the state of New Hampshire can begin. Brook trout numbers may not increase, since rivers are typically at capacity, but Masterson expects some changes.

"With increased access to spawning and rearing habitat, we may not see more fish, but more genetically diverse fish, which will help them persist into the future," she said.

Just like the rich history around the dam’s construction, we look forward to the lasting benefits to people, fish and wildlife created by the unobstructed flow of the Mohawk River.